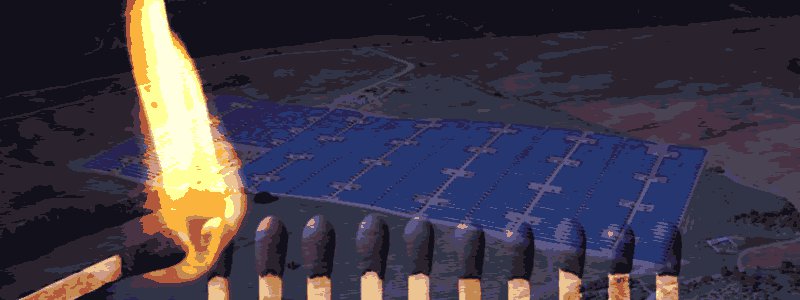

Historically, the deployment of solar PV has been financed through the utilization of governmental support schemes, such as feed-in tariffs (FiTs). However, over the last decade, the ever-decreasing system costs for solar installations have led to radical changes in the solar industry. As more and more solar PV capacity is now being connected to the grid, especially in Spain and other southern European countries, the impact of the so-called “solar cannibalization effect” starts to become a more prominent threat.

The solar cannibalization effect takes place when the market reaches a point where every new PV plant could potentially cause a negative impact on the financial performance of older solar plants that have already been commissioned. Multiple studies have shown that increased penetration of renewables tends to decrease wholesale power prices. In some markets where wholesale power prices are relatively low, such as Germany and the UK, wholesale prices have even reached a point where they dropped below zero. This happened in the UK last year, when a period of higher-than-forecasted solar power generation drove wholesale prices into negative territory. In this sense, solar cannibalization is seen as a self-induced effect coming from the PV industry itself, instead of being induced by competitive pressures by other technologies.

Why do market players need to know this? Let’s take the case of Spain as an example.

Between 2008 and 2010, the Spanish government found themselves in a difficult situation because more capacity was connected to the grid than they expected, which put massive budgetary pressure on the country, especially due to the tariff deficit. Solar cannibalization was never really a topic of discussion in Spain at that moment, since the country already had, and still has, one of the highest wholesale electricity prices in Europe.

However, the Spanish PV market is now booming once again and is starting to shift away from being completely dependent on the country’s regulatory framework, towards being a market where lenders and investors are willing to sell their electricity on the spot market against merchant risk. A few weeks ago, IRENA announced that Spain has between 10-12 GW of PV capacity in the ready-to-build phase, with another 15-20 GW under development. That means that multiple GWs of PV capacity will be connected to the grid in the coming years, which has now brought forth fears of solar cannibalization. It also begs the question: Are these multi-GW targets going to lead to a massive price drop? And: is there a tipping point for Spain?

In general, the vast majority of investors require contracted revenues. In the current situation, which lacks feed-in tariffs (FiTs), this translates into PPAs. However, the number of bankable off-takers in Spain is limited. The few off-takers in the market that are able to get the prices they want, can only do so because they have considerable bargaining power. Ultimately, this buyer’s market leads to limited returns for PV projects.

When it comes to long-term contracts, things can be done to stimulate off-takers to hedge prices over longer turnouts. The government could do this by implementing fiscal or accounting incentives, or by organizing new renewable energy auctions. In fact, last week, the Secretary of State announced that renewable energy auctions for more than 3 GW per year will definitely take place. Whatever the option, these levers share a common denominator, which is that they imply regulatory risk. It is also interesting to note that many players are currently still involved in arbitration proceedings with the Spanish state, due to past changes to the country’s regulatory framework. All of this shows that, in practice, the choice will be between regulatory risk or merchant risk, or even a combination of both.

This begs another important question:

Are the players with significant financial resources, both equity and debt, willing and able to take merchant risk?

What has been seen so far is a movement from the contracted end of the market towards the merchant end. However, that transition has - for the time being - been slow and painful. This implies that the expected drop in spot prices driven by the massive volume of renewable coming online may take longer than anticipated, even without disruptive events on the demand side, like an influx in the uptake of electric vehicles.

Things could change rapidly, though, especially for lenders and investors, due to excess liquidity and a need for high returns. It is also believed that, even if the announced auctions see the light of day, merchant elements will need to be incorporated into the legislation for new projects, as the auctions will probably result in very low power prices, which will be in need of merchant exposure to meet return hurdles.

All things considered

We can conclude that the effects of solar cannibalization will not likely hinder the growth of the Spanish solar market, as long as PV remains competitive against the conventional energy sources that still account for the bulk of generated power in the country. It is safe to say that the point in time when one marginal unit of PV capacity would be capable of causing a collapse in power pricing, thus resulting in solar cannibalization, remains very far away.

Learn more about the intricacies of the maturing Spanish solar PV market at 'Solar Market Parity Spain 2019'. This 1-day conference, taking place on 14 March 2019 in Madrid, aims to connect the right players in a market on the verge of a solar (r)evolution.