-

Indonesia will need to install 45GW of renewables — including 6.4 GW of solar capacity — for clean energy to account for 23% of the national energy mix by 2025, according to Maritje Hutapea, director of Various New and Renewable Energy under the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (MEMR)

-

Total installed generating capacity on the main islands of Java, Bali and Sumatra stood at roughly 41 GW at the end of 2015, according to state-run utility PT PLN (Persero)

In December, MEMR Minister Ignasius Jonan announced plans to send officials to the United Arab Emirates. Impressed by the record-low bid of US 2.99 $cents/kWh that was submitted last May for the 800MW third phase of Dubai’s 5 GW Mohammed bin Rashid al-Maktoum project, Jonan is eager to identify ways to reduce the FIT prices the MEMR announced last July.

“There is uncertainty over how much they will reduce these FITs,” says Jakarta-based renewables consultant Andre Susanto.

In July, the government raised hopes for the PV sector when it issued MEMR Regulation 19/2016, which established a 250 MW solar development quota, as the first phase of a planned 5 GW rollout.

“The regulation was a good price signal and commitment to the market,” Susanto says.

However, prospective developers have not been been idly waiting for a final decision on subsidies. Over the past 18 months, the number of companies that have negotiated bilateral agreements with PLN has surged.

“People have been getting tired of waiting for the government to issue a new regulation,” says Susanto.

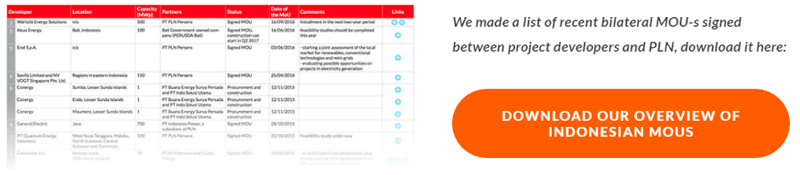

In the past 12 months alone, a range of companies — including Conergy, Enel and NV Vogt — have signed memoranda of understanding (MOUs) with PLN, beyond the scope of the proposed FIT scheme.

“PLN has been indicating that it is willing to do more of these business to business deals, as long as it makes financial sense,” says Susanto.

First Steps

However, beyond the islands of Java, Bali and Sumatra, Indonesia’s grid system is spread across a vast chain of geographically remote islands. This makes it particularly challenging to assess the prices at which solar can be developed and sold throughout the archipelago.

“There’s not a single price because there are many isolated grids. Each grid has its own price and costs, and they range from US 6 cents/kWh to US 25 cents/kWh,” Susanto says.

Developers have been signing MOUs with PLN for several years, particularly since 2013, when the introduction of a now-defunct reverse auction system spurred interest. However, the pace at which PLN has been signing these agreements has accelerated since 2015, according to Susanto.

Such arrangements are not full-fledged PPAs, with Rome-based Enel characterizing the MOU it signed with PLN last June as “a first step in developing an operational presence” in the country.

“Before, people were just signing MOUs and then not doing anything. All they were doing was trying to find local partners,” says Susanto, noting that a growing number of players are now looking for land, conducting site surveys and talking to local grid operators. “Activity surrounding the MOUs that are being signed has been much higher.”

Pain Points

However, there are few established procedures for negotiating these agreements at this stage. Developers must therefore feel their way through the process, initially by arranging meetings with PLN’s planning and renewable-energy divisions, which are overseen by director of corporate planning Nicke Widyawati, who reports directly to CEO Sofyan Basir.

“You have to customize what it is that you want to talk about — what it is that you want to develop,” Susanto advises.

Developers should carefully consider how they approach PLN. At the beginning of such talks, they should avoid asking about whether they can install specific amounts of capacity at specific sites, Susanto says.

“PLN does not respond to that well because Indonesia’s grid is very fragmented,” he explains, suggesting that it would be better to start by expressing a broad interest in solar development before asking how projects could be built in a way that helps the utility.

By initially framing an interest in project development within the context of PV-diesel hybrid installations, as well as storage solutions, companies can also broach PLN’s concerns about issues such as cost reduction and grid integration.

“That would be a very good ‘in’ for PLN, because those things are their biggest pain points,” Susanto says.

Mutual Benefits

PT Len Industri (Persero), among the first companies to sign a PPA with PLN, says negotiations generally take about six months.

“The process is smooth enough,” says a spokesperson for the Bandung-based company, which is already running a 5 MW project in East Nusa Tenggara province.

As an officially accredited IPP, Len Industri builds and runs solar projects, backed by a US $11.2 million war chest. It is then able to feed the electricity it generates into PLN’s grid network as it wishes, without needing to worry about storage.

“(The PPA process) is not very hard because PLN and the government want companies to invest,” the spokesperson says.

Nikesh Sinha, director of Singapore-based solar developer NV Vogt, agrees that the path from MOU to PPA generally takes about half a year, but says companies should focus on communicating how an arrangement with PLN would be mutually beneficial.

“When we do bilateral negotiations with PLN, we’re not talking about any subsidies. We’re talking about what their current pricing is and whether we can give them competitive pricing, which would then allow them to replace one source of energy with another,” he explains.

Only a portion of the 150 MW of capacity that NV Vogt intends to develop in Indonesia will likely be built under the FIT, with many of its planned projects to be installed via bilaterally negotiated PPAs.

The company is now in the process of submitting the feasibility studies that will lead to it its first PPAs.

“Indonesia is definitely an early-stage market,” Sinha acknowledges. “But the advantages of that is that once you’re there and established, you can probably build a large business.”